I had never been to Fibre East before, but last weekend I attended their virtual event (for those of you who may not know, Fibre East is a fibre festival in the East of England dedicated to promoting wool and textiles). I’m all for supporting small businesses and I get very inspired by other people’s fibre finds, so I thought this week I would do a little fibre haul, as everything was dispatched so quickly it all arrived within the week!

Disclaimer – I am not in any way affiliated with any of the companies mentioned in this post- just very happy with the experience they gave. Links to websites are provided for reference.

Yarn

I try to be very selective when it comes to buying yarn as I have a stash of fleeces waiting to be spun, so it has to be different to justify me buying it! The beautiful green skeins (and complementary teabag!) are from Knit Me Sane, one is a Merino/Linen blend which I’m excited to work with and the other is made from Polworth wool. I also purchased a ‘scrappy bag’ of merino/mohair wool in various colours to experiment with from the Wensleydale Sheep Shop.

Fibre

I tried to be strict with myself when it came to fibre, but couldn’t resist buying a raw Romney fleece from Romney Marsh Wools (it’s so soft I can’t wait to work with it!). I also bought some lovely fibre blends from Yarns from the Plain – 2 are shetland/tussah silk blends (I’ve not tried spinning silk blends before) and the other is a Hill Radnor, a rare British breed that I’ve not yet explored.

I also decided to buy some Angora fibre to try spinning from the National Angora Bunny Club. I’m a big believer in animal welfare, so it was important to me that I purchased Angora that was traceable and had been shorn ethically. The proceeds the club recieves from selling the fibre are used to pay for food and vaccinations for the rabbits.

Miscellaneous Items

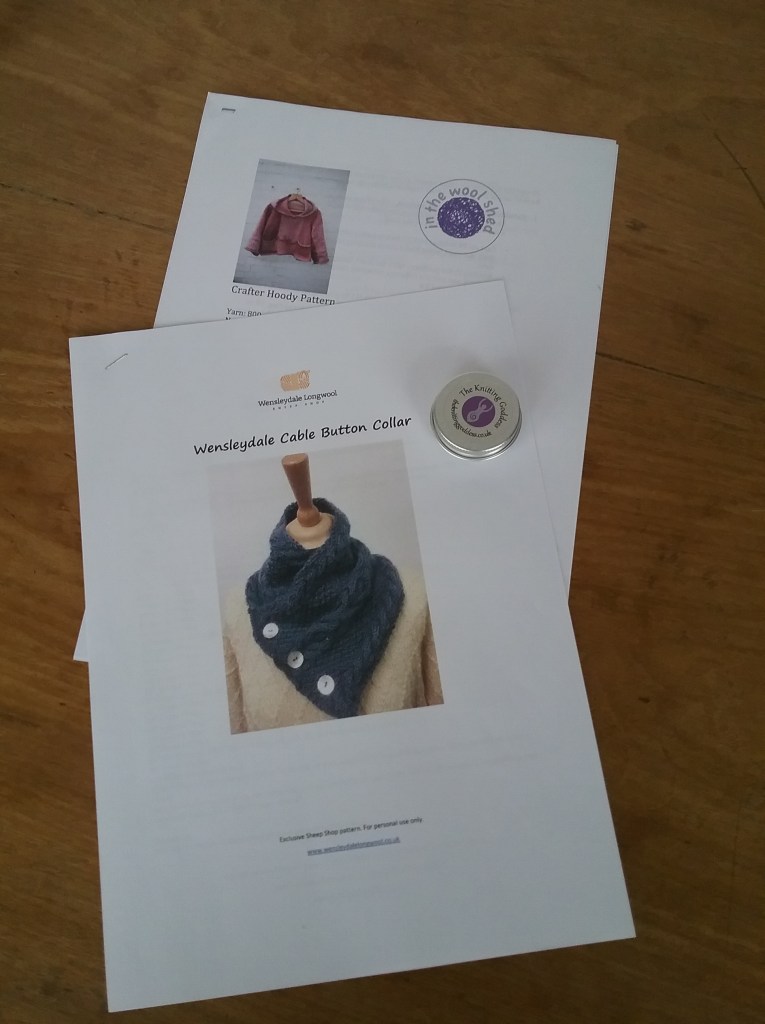

I purchased a couple of simple knitting patterns to try – ‘Crafter Hoody’ from In The Wool Shed and a cable collar pattern from the Wensleydale sheep shop (I’ve never attempted cable before and this looked like a good starter project). Whilst on their website I thought it was high time I got myself some proper stitch markers instead of using paperclips, so bought some little wooden ones with Wensleydale Sheep on.

That’s the end of my little Fibre East haul, I ‘came away’ with lots of inspiration (now I’ve just got to find the time to fit everything in!). At the time of writing this, Fibre East still has a full list of previous exhibitors with links to their websites, so I definitely recommend browsing if you’re looking for some creative inspiration or need to add to your stash and want to support small independent businesses.

Happy Crafting!