For the past few years I’ve been leading a double life, exploring wool witchery while also undertaking a human geography degree. It was inevitable that at some point these two things would interconnect and the following essay exploring the Anthropocene (a proposed geological epoch defined by humankind’s impact on the environment) through the social and cultural history of wool was the result:

Introduction

Wool is both a natural resource and a representation of the change in values that underpins most Anthropocene arguments. Caught in the entanglements between human and other non-human ‘objects’; it would be impossible to discuss wool without also discussing sheep, just as it is impossible to discuss the historic wool industry without also exploring the rise of colonial cotton production. Focusing on the UK, whose woollen heritage is well documented, I explore the changes in value to resources, work and technology throughout time; illustrating that the Anthropocene is not only about the physical human impact on the environment as first put forward by Earth’s System’s scientists (Crutzen & Stoemer, 2000), but also the underlying political and economic systems that propose certain narratives (Bonneuil, 2015). As a symbol of bygone eras, wool advises caution, but seen as an object of resistance it offers some hope amongst eco-catastrophist outlooks in this precarious epoch.

Sheep: Man’s Second-Best Friend

Sheep have been living alongside humans for thousands of years; the bones of Soay sheep on the Island of St Kilda today, closely resemble those found at Bronze age sites on the British Mainland (Clutton-Brock, 2012; Ryder, 1964), suggesting these sheep moved with early settlers to the islands. While today’s Soay sheep are similar to their ancestors, the genomes of many other domestic sheep are significantly different. Archaeological evidence suggests humans have been making textiles from wool since the late Neolithic/early Bronze Age (Grömer, 2004) and during thousands of years of sheep domestication, we have actively engaged in selective breeding based on desirable characteristics (low kemp/high wool, fine fibre diameter etc.). Clutton-Brock (1992) argues that these biological changes occur as a result of the cultural conditions imposed by the human regime. As we domesticate sheep and use their wool, both sheep and their fibre become property, subject to ownership and economically valuable; they are commodified as humans separate themselves from a perceived ‘nature’. The result of this selective breeding for quality wool yield, means that while primitive breeds can shed their fleece, others require shearing for their health (BBC, 2021; 2023). While high wool yield was valued, humans adapted to careful shepherding, living alongside sheep as companion species (Haraway, 2003), and collectively changing the wider landscape to suit agriculture. However, as the value of wool has declined in favour of meat production (Masters & Ferguson, 2019), this relationship unravels and shearing becomes costly.

Despite centuries of selective breeding sheep have not become homogenous; there are over 60 different pure breeds of sheep within the UK (British Wool Board, 2010), each with different biological characteristics and adaptions to a multitude of British environments, however it was only recently that this genetic diversity has been valued. The near extinction of the Norfolk Horn made them the first entry into Solly Zuckerman’s gene bank at Whipsnade Zoo and the breed would become a founding member of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST) in 1971 (Monahan, 2024). Today greater importance is placed on genetic diversity since it acts as extinction insurance, however the RBST still lists 27 sheep breeds on their watchlist (RBST, 2021). Gene banks and breed conservation are direct responses to the precarity of the Anthropocene, however this also raises ethical questions; does preserving genetic diversity in gene banks reduce support to maintain it in the ‘wild’ (the RBST faces challenges from both policymakers and farmers (Evans & Yarwood, 2000; Mansbridge, 2004)), and does a reliance on science as a solution to institutional problems lead society too far into eco-modernist approaches?

Malhi (2017) discusses how adopting an early Anthropocene narrative, focusing only on detectable human presence, undermines the need for urgency and risks simply renaming the Holocene. However, despite humans’ early curation of sheep genetics, it is the assigning and reassigning of widespread economic value to sheep/wool over time within capitalist systems that is responsible for characterising the cultural and political norms that have led us into an age of extinctions and conservation in the name of ‘science’.

Work & Industry: The Rise and Fall of Wool

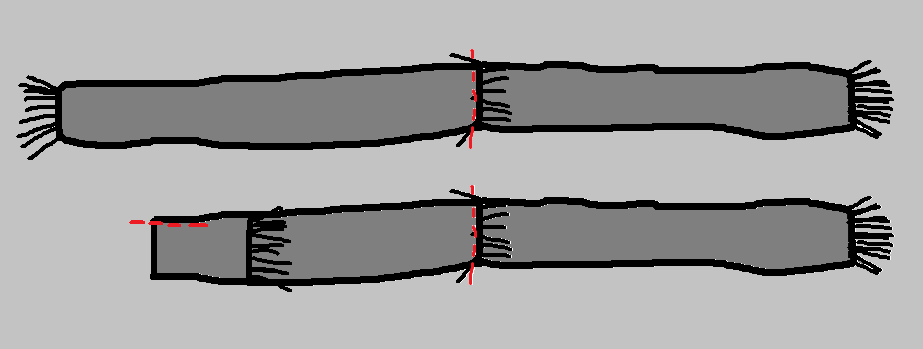

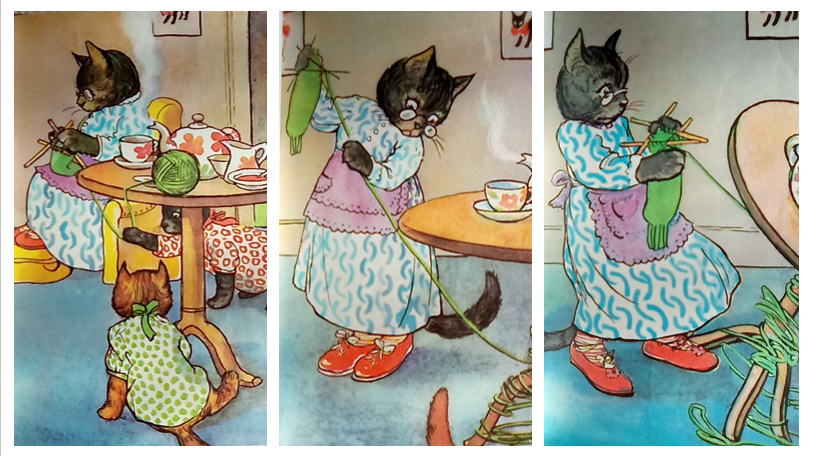

Wool is representative of institutional changes, particularly the value of different types of work. Prior to the industrial revolution, woollen textile manufacture was undertaken as piecework facilitated by wool merchants; a style of working that was particularly conducive to flexible working practices and allowed women to participate in the workforce, alongside taking part in childcare for example. Wool was essential to the UK’s pre-industrial economy, so much so that governments introduced protectionist measures such as the Capper’s Act of 1571, the Burial in Wool Acts from 1666, and multiple import and export taxes (Coulthard, 2021). To represent the importance of wool to national identity and the control the state attempted to impose over woollen textile production, the speaker in the House of Lords had been sitting on the Woolsack since the 14th Century; however, despite the perceived governmental control, piecework allowed spaces of resistance to emerge, from female dominated spinning bees where knowledge was shared, to the lucrative business of wool smuggling (this was particularly prevalent at Romney Marsh with the brutish smugglers hailed as dashing heroes in literary representations (Hollick, 2019)). At both local and national scales, wool was important, and skilled craftmanship was also highly valued. This pre-industrial textile industry generated significant wealth, which Allen (2009) argues was a key driver in funding technological innovation, one of the reasons Britain was first to industrialise, funding its colonial goals and spelling the beginning of the end for wool.

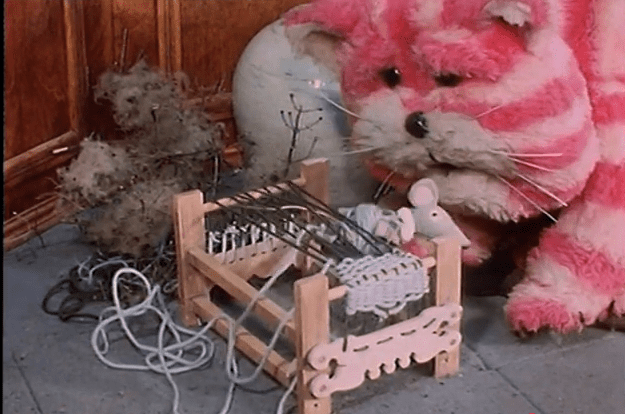

In the mid-17th Century James Hargreaves patented the Spinning Jenny, an industrial device of significant time saving (before the advent of the spinning wheel one worsted cloth took approximately 165 hours to make (Monahan, 2024)). The combination of established European colonialism, decreased production times, and changing fashions as a wealthy elite adopted ‘Oriental’ cotton fabrics, became a slow catalyst to textile industrialisation in the UK. The wool and cotton industries became locked in a battle; politicians were wary of losing the well-established wool industry, while entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to exploit the ‘ghost acres’ provided by cotton plantations and price the Indian handloom industry out of global markets (Hills, 1970, ch.1). New machines were large and manufacture moved from the home into factories, making it easier for the powerful elite to observe workers and disrupt social organisation (Moore, 2002). During the Industrial Revolution, the woollen industry attempted to hold its ground in the home while cotton textile production was concentrated in factories. Despite efforts of the Luddites, skilled woollen weavers could not compete with machines and faced an 80% reduction in wages described as ‘a classic example of the triumph of “economic progress” at the expense of “social welfare”’ (Lipson, 1965, p.194). For the industrial elite, low skilled workers across the empire were now in demand; considered expendable and easy to control, while British women were compelled to enter the new industrial workforce or conduct unpaid domestic labour (Nicholas & Oxley, 1993; Foster & Clark, 2018), the gender inequalities from which are still prevalent in informal care provision for example (Dahlberg et al., 2007).

For historical and political geographers, assigning economic value to both resources and/or labour is core to the argument that the Anthropocene did not begin with human geological impact on the environment, but the organisation of social structures that facilitated exploitation of both the environment and people (Moore, 2015; Barry & Maslin, 2016). Without capitalist involvement in the woollen textile industry, might industrialisation and craftsmanship developed more equitably, and would wool have endured for longer?

Compost, Crafters & Technological Advancement

The Great Acceleration is credited with inspiring a throwaway consumer culture, as wool was replaced with cheaper, more ‘modern’ oil derived fabrics such as nylon during the 1950s/1960s. During this time wool was described as high maintenance and scratchy; a symbol of the past, while synthetic fabrics were advertised as ‘easy-iron’ and ‘quick-drying’ (Schneider, 1994). This fossil fuel driven narrative was incredibly effective, with over 69% of all fibre production today being synthetic, and despite evidence of the environmental harm these plastic fibres can do, this sector continues to grow (Brooks, 2015; Changing Markets, 2024). In response to these environmental problems and the need for sustainable fibres, scientists have in many ways been tasked with reinventing the wheel. Wool is a keratin based fibre and it’s molecular structure makes it insulative, flame resistant, strong, flexible and biodegradable (British Wool, 2023). Wool outperforms synthetics and other natural fibres in insulation and temperature regulation, both for clothing and interior design (Abedin & DenHartog, 2023; Rahm, 2023), yet carbon footprint research remains focused on Life Cycle Assessments, which prioritise footprints in early manufacturing rather than throughout the whole life cycle, a system which favours synthetic fibres and leads to technocentric solutions (Rubecksen & Steinert, 2024). However wool provides an opportunity for new and old to merge, particularly in the clean-up of oil spills where wool’s high absorbency is more effective than existing methods which rely on either chemicals or plastic skimmers (Lim & Khimji, 2013), though widespread adoption of this technology requires a cultural shift within the petrochemical industry.

With sustainability increasingly influencing consumer habits, wool has recently undergone a rebrand. Designer labels such as Chanel have been marketing wool (particularly merino) as a luxury fibre, resulting in an identity dualism; wool is either considered by consumers to be ‘itchy’ and ‘dull’ (Hebrok et al., 2016), or ‘sustainable’ with greater perceived luxury value (Guercini & Rafagni, 2013). High designer price tags make wool unaffordable to many consumers, however the British Wool Marketing Board pay only £1/kg of raw fleece (British Wool, 2024) with transport being at the farmers’ expense. This has led farmers to compost or burn fleece to dispose of it cheaply and protest, releasing more carbon into the atmosphere (BBC, 2020, 2024). Despite high domestic wool availability, the UK imports over 23 million kilograms of wool (Bedford, 2024), raising animal welfare concerns surrounding the treatment of sheep in Australia for example where mulesing (the removal of skin from the hindquarters to reduce flystrike) is still legal, and presenting another barrier to ‘ethical’ consumption, as wool caught in global trade networks has limited traceability.

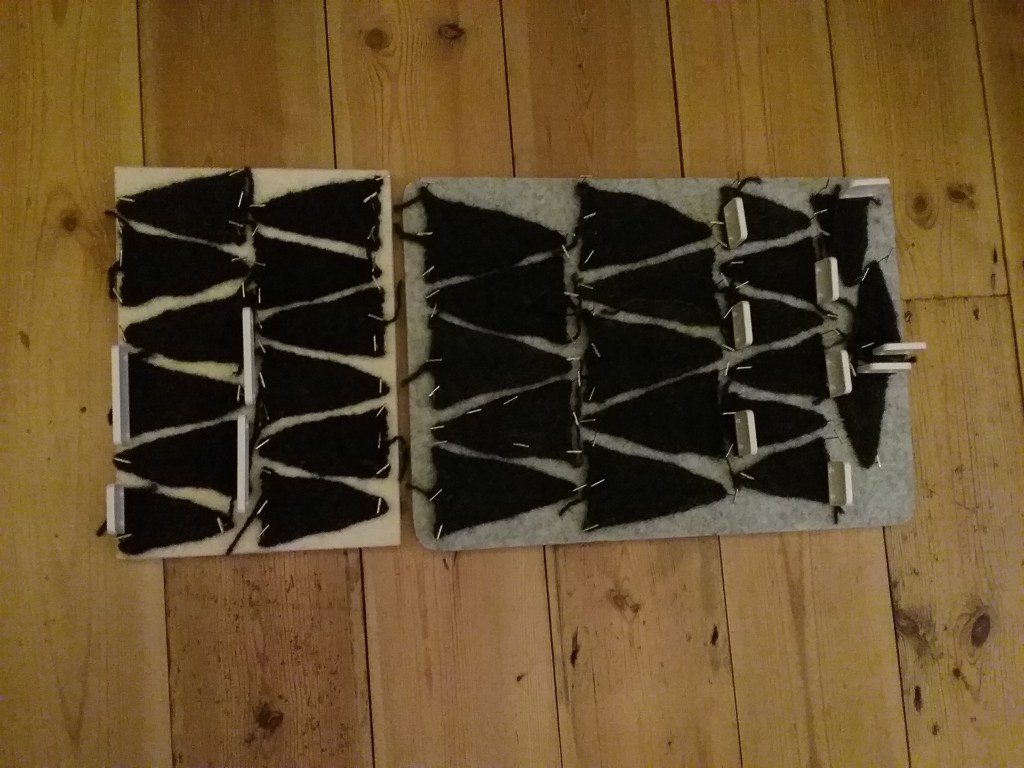

There is however hope; crafters and designers are increasingly using wool as an object of resistance and valuing local production as part of heritage and identity (Jones et al., 2019). The Campaign for Wool (patroned by the King), Wovember and British Wool month; raise awareness in an attempt to change the culture, while Shetlanders have been finding alternative ways of teaching children lace & Fair Isle knitting to retain its ‘intangible cultural heritage’, since knitting was removed from the curriculum due to spending cuts (Robertson, 2010; ICH Scotland, 2024). There is a place for creativity and innovation in the Anthropocene, particularly in reconnecting us with the non-human. Craft exists beyond mass production and values indigenous/local knowledge in equal measure to scientific discourse (Tarcan et al., 2023); it can help envision multispecies futures (Uğur Yavuz et al., 2024) and already has solutions to some Anthropocene problems, including instigating changes to cultures of value and consumption (Brooks et al., 2017). In this way wool offers an opportunity for individuals to engage with smaller scale participatory practice in the Anthropocene, constructing new, more equitable and caring relationships with nature and wider society.

Conclusion

I write in favour of wool, though I acknowledge it is by no means a magical solution to all environmental problems (the meat and livestock industries have their own ethical and environmental dilemmas), nor should it be used as a way for further justifying mass consumption. Wool supports arguments for multiple Anthropocene onsets; but above all highlights the importance of changing values and the entanglements of the non-human within the wider political, economic and cultural systems throughout time, as being a defining feature of this new epoch. Wool offers a path out of the Anthropocene; we have created power structures and consumerist habits that continue to degrade environments worldwide (Kidner, 2021), but these were socially constructed and can be re-made in more equitable ways. We have changed the genetics of sheep to suit our requirements and therefore have a responsibility to them, as Latour (2011) discusses – moving forward requires a change of perspective.

Technological advancement has become the benchmark for progress; however, it is not the only option. Wool offers an opportunity for widespread interdisciplinary engagement between science and the arts, bringing eco-modernist narratives out of epistemic communities where knowledge enables the powerful elite to retain control, and into the public sphere where it can be critiqued and debated. Historically the decisions that led to the devaluing of wool, work and nature, have been made by an elite few who monopolise economic spaces, but if we are to move forward, we must find ways to involve as many voices as possible. Wool highlights historical fallacy and inequalities that we can learn from and like wool in the present day, we have two options; can we ‘rebrand’ and place greater value on existing technologies, or will we too end up on the compost heap?

If you wish to use this essay please use the following reference:

Patterson, A. (2024) ‘Wool & The Anthropocene: An Essay’, Loose Ends Fibre, 9 November. Available at: https://looseendsfibre.co.uk/2025/11/09/wool-the-anthropocene-an-essay/.

With thanks to Dr Martin Mahony & Dr Dave McLaughlin who teach the wonderful Human Geographies of the Anthropocene module, and to Mark Goldthorpe for featuring my short piece about wool on the ClimateCultures website, which houses contributions from academics and creatives.

Reference List:

Abedin, F. and DenHartog, E. (2023) ‘A new approach to demonstrate the exothermic behavior of textiles by using a thermal manikin: Correction methods of manikin model’, Polymer Testing, 128, p. 108195. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108195.

Allen, R.C. (2009) The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. 1st edn. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816680.

Barry, A. and Maslin, M. (2016) ‘The politics of the anthropocene: a dialogue’, Geo: Geography and Environment, 3(2), p.22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.22.

BBC (2020) ‘Coronavirus: Shepherd scraps wool harvest due to price slump’, BBC News, 22 July. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-53501671 (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

BBC (2021) ‘New fleece of life for sheep with 35kg coat of wool’, BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-australia-56189981 (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

BBC (2023) ‘Resc-ewed: Britain’s loneliest sheep saved from shoreline’, BBC News, 4 November. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-67321305 (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

BBC (2024) ‘Sheep wool torched in protest over “measly” prices’, BBC News, 13 February. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-lincolnshire-68253397 (Accessed: 9 April 2024).

Bedford, E. (2024) UK wool imports 2023, Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/412191/united-kingdom-uk-wool-imports/ (Accessed: 22 October 2024).

Bonneuil, C. (2015) ‘The Geological Turn: Narratives in the Anthropocene’, in The Anthropocene and the Global Environmental Crisis: Rethinking modernity in a new epoch. 1st edn. Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743424.

British Wool (2023) ‘The structure of wool fibres’, British Wool, 1 March. Available at: https://shop.britishwool.org.uk/the-structure-of-wool/ (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

British Wool (2024) Price Indicator | British Wool. Available at: https://www.britishwool.org.uk/price-indicator (Accessed: 9 April 2024).

British Wool Marketing Board (ed.) (2010) British sheep & wool: a guide to British sheep breeds and their unique wool. Oak Mills, West Yorkshire: British Wool Marketing Board.

Brooks, A. (2015) Clothing poverty: the hidden world of fast fashion and second-hand clothes. London, UK: Zed Books.

Brooks, A. et al. (2017) ‘Fashion, Sustainability, and the Anthropocene’, Utopian Studies, 28(3), pp. 482–504. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5325/utopianstudies.28.3.0482.

Changing Markets (2024) Fossil fashion: the hidden reliance of fast fashion on fossil fuels • Changing Markets, Changing Markets. Available at: https://changingmarkets.org/report/fossil-fashion-the-hidden-reliance-of-fast-fashion-on-fossil-fuels/ (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

Clutton‐Brock, J. (1992) ‘The process of domestication’, Mammal Review, 22(2), pp. 79–85. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.1992.tb00122.x.

Clutton-Brock, J. (2012) ‘Arrival of Domesticates in Europe’, in Animals as domesticates : a world view through history. East Lansing : Michigan State University Press.

Coulthard, S. (2021) A short history of the world according to sheep. London: Head of Zeus.

Crutzen, P.J. and Stoemer, E.F. (2000) ‘The Anthropocene’, Global Change Newsletter, 41, pp. 17–18.

Dahlberg, L., Demack, S. and Bambra, C. (2007) ‘Age and gender of informal carers: a population-based study in the UK: Age and gender of UK carers’, Health & Social Care in the Community, 15(5), pp. 439–445. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00702.x.

Evans, N. and Yarwood, R. (2000) ‘The Politicization of Livestock: Rare Breeds and Countryside Conservation’, Sociologia Ruralis, 40(2), pp. 228–248. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00145.

Foster, J.B. and Clark, B. (2018) ‘Women, Nature, and Capital in the Industrial Revolution’, Monthly Review, pp. 1–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-069-08-2018-01_1.

Grömer, K. (ed.) (2004) ‘“Hallstatt Textiles” Technical Analysis, Scientific Investigation and Experiment on Iron Age Textiles’, in. Hallstatt Textiles, Hallstatt/Austria. Available at: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/105835128/2005_20Hallstatt_Conference_BAR_202005_-libre.pdf?1695207476=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DHallstatt_textiles_technical_analysis_sc.pdf&Expires=1731324010&Signature=ajjLziQHOGd9XNTpChY3tr8YzdBurZQ0qn8BSlDt1XiW-8qJOBY3GJhzqRP~zoDCOA2Ez4EguKAOz9xY8SsHzj2nLOvg2dFiHjqCApCR90MJlwfvR1cIK-rbsHsaMZtgFIMWjRk1UMCWkHeFuNFmOdPcKxxQvyTVkK-EJjQVt5XBLS~ojJyMevhIw-0zlPjwwr7Hd35NviqHZmgE2BrEFCv1HtZ6CQPhFaqPmPJnE7fXeGLuGShOqENSia1SJRWv9TVzU–spSiocpurlOe8WO7dQEBE6VuyNEoiaM89qiZJGAE-hR3VT-8kKwg3F8~yEI-9QTrJGOInLPGD9HiNtA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA#page=125 (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

Guercini, S. and Rafagni, S. (2013) ‘Sustainability and Luxury: The Italian Case of a Supply Chain Based on Native Wools’, The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 52, pp. 76–89.

Haraway, D.J. (2003) The companion species manifesto: dogs, people, and significant otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press (Paradigm, 8).

Hebrok, M., Klepp, I.G. and Turney, J. (2016) ‘Wool you wear it? – Woollen garments in Norway and the United Kingdom’, Clothing Cultures, 3(1), pp. 67–84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1386/cc.3.1.67_1.

Hills, R.L. (1970) Power in the Industrial Revolution. Manchester: Manchester U.P.

Hollick, H. (2019) Life of a smuggler: fact and fiction. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

ICH Scotland (2024) Shetland Knitting | ICH Scotland Wiki. Available at: https://ichscotland.org/wiki/shetland-knitting (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

Jones, L., Heley, J. and Woods, M. (2019) ‘Unravelling the Global Wool Assemblage: Researching Place and Production Networks in the Global Countryside’, Sociologia Ruralis, 59(1), pp. 137–158. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12220.

Kidner (2021) ‘Anthropocene Subjectivity and Environmental Degradation’, Ethics and the Environment, 26(1), p. 57. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.26.1.03.

Latour, B. (2011) ‘Love Your Monsters: Why we must care for your technologies as we do our children’, Breakthough Journal, 2(11), pp. 21–28.

Lim, P. and Khimji, K. (2013) ‘The Golden Fleece: Innovative Ways to Clean up Oil1’, Canadian Young Scientist Journal, 2013(2), pp. 18–23. Available at: https://doi.org/10.13034/cysj-2013-005.

Lipson, E. (1965) The History of the Woollen and Worsted Industries. Frank Cass & Co. LTD.

Malhi, Y. (2017) ‘The Concept of the Anthropocene’, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), pp. 77–104. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060854.

Mansbridge, R.J. (2004) ‘Conservation of farm animal genetic resources – a UK national view’, BSAP Occasional Publication, 30, pp. 37–43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263967X00041926.

Masters, D.G. and Ferguson, M.B. (2019) ‘A review of the physiological changes associated with genetic improvement in clean fleece production’, Small Ruminant Research, 170, pp. 62–73. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2018.11.007.

Monahan, J. (2024) Norfolk Horn: The Saga of a Rare Breed, It’s Place and It’s People. Anglia Print Ltd.

Moore, J.W. (2002) ‘Remaking Work, Remaking Space: Spaces of Production and Accumulation in the Reconstruction of American Capitalism, 1865–1920’, Antipode, 34(2), pp. 176–204. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00235.

Moore, J.W. (2015) Capitalism in the web of life: ecology and the accumulation of capital. London: Verso.

Nicholas, S. and Oxley, D. (1993) ‘The Living Standards of Women during the Industrial Revolution, 1795-1820’, The Economic History Review, 46(4), p. 723. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2598255.

Rahm, P. (2023) The anthropocene style. Available at: https://arodes.hes-so.ch/record/12937?ln=en&v=pdf (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

RBST (2021) Sheep watchlist, Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Available at: https://www.rbst.org.uk/Pages/Category/sheep-watchlist?Take=28 (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

Robertson, J. (2010) Era of knitting lessons in schools to come to an end as cash saving is agreed, The Shetland Times. Available at: https://www.shetlandtimes.co.uk/2010/05/06/era-of-knitting-lessons-in-schools-to-come-to-an-end-as-cash-saving-is-agreed (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

Rubecksen, H.S. and Steinert, M. (2024) ‘Man-Made Adaptations to Wool in the Anthropocene – Proposed Reference Framework for Fibre Comparison’, in Proceedings of NordDesign 2024. NordDesign 2024, Reykjavik, Iceland, 12th – 14th August 2024, The Design Society, pp. 577–587. Available at: https://doi.org/10.35199/NORDDESIGN2024.62.

Ryder, M.L. (1964) ‘The History of Sheep Breeds in Britain’, The Agricultural History Review, 12(1), pp. 1–12.

Schneider, J. (1994) ‘In and Out of Polyester: Desire, Disdain and Global Fibre Competitions’, Anthropology Today, 10(4), p. 2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2783434.

Tarcan, B., Nilstad Pettersen, I. and Edwards, F. (2023) ‘Repositioning Craft and Design in the Anthropocene: Applying a More-Than-Human approach to textiles’, Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 10(2), pp. 26–49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31273/eirj.v10i2.973.

Uğur Yavuz, S., Bektaş, M. and Ayala Garcia, C. (2024) ‘FERAL WOOL. Designing with a vibrant matter with care and cosmoecological perspective in times of troubled abundance’, INMATERIAL. Diseño, Arte y Sociedad, 9(17). Available at: https://doi.org/10.46516/inmaterial.v9.204.